In the ‘Belly of the Beast’

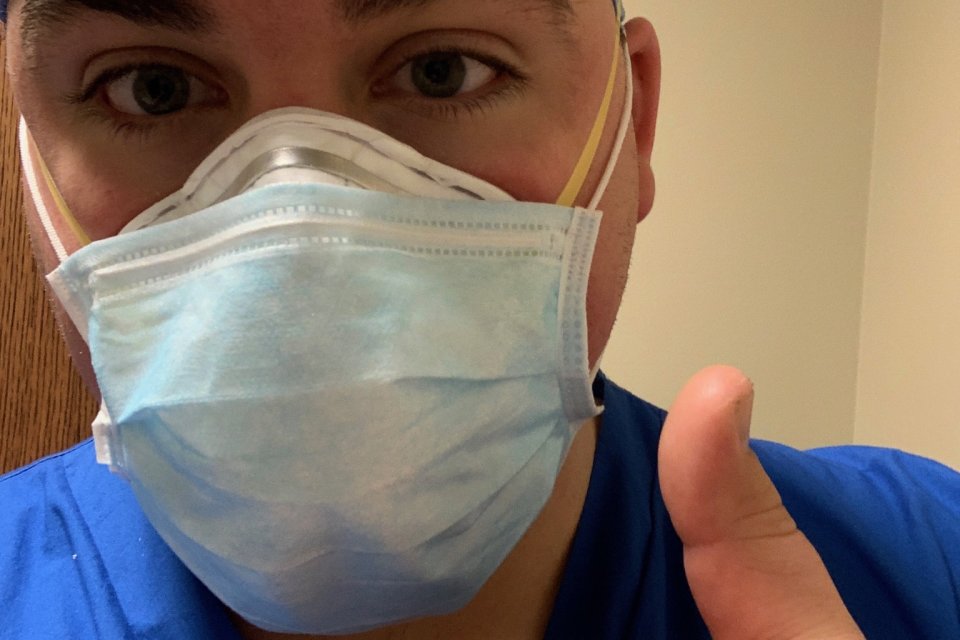

A crisis relief ICU nurse just outside New York City, Nick Hallett ’18 is treating some of the country’s sickest COVID-19 patients. Here, he shares what he’s learned after six grueling weeks on the job.

As an ICU nurse outside New York City, nursing grad Nick Hallett ’18 is more than on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I’m in the belly of the beast,” says Hallett, who spends up to 60 hours a week treating some of the sickest COVID-19 patients in one of the country’s hardest hit regions.

Just 10 minutes from Manhattan, Hallett's hospital transitioned to an all-COVID facility in March, shortly before Hallett left his job as a cardiopulmonary ICU nurse at Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse to answer the desperate call for nurses downstate. He quickly secured a contract position with Aya Healthcare, a travel nursing agency that assigned him to a crisis relief position in the understaffed hospital.

Now, after nearly six weeks working in a makeshift ICU (one of nine such units in the hospital, including one in the former cafeteria), Hallett has seen firsthand the devastation and heartache of the pandemic on a deeply personal level.

On a rare day off, Hallett shared what this experience has taught him about COVID-19, the nursing profession—and himself.

The virus is unpredictable—and probably scarier than we think.

By now, the general public is familiar with the telltale signs of COVID-19: fever, cough, shortness of breath. But in the worst cases, says Hallett, the virus attacks the body in strange and even more devastating ways.

“We’ve seen many, many patients die from cardiac arrest,” says Hallett. “We’re just learning now how the virus affects the heart, the lungs, and the kidneys, thickening the blood and causing blood clots.”

For Hallett and his team of doctors, this makes treating the virus like shooting a moving target.

“We will devise a treatment plan that has to completely change the next day because of how this virus progresses in the body,” he says. “It’s like nothing we’ve seen before.”

Nurses are improvising.

Compared to most hospitals, says Hallett, his facility has not experienced the dire shortage of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) so widely reported in the news. But there have been challenges.

When Hallett arrived at work one day to find only size-small N95 face masks, a colleague suggested buying his own reusable respirator online. Sold out nearly everywhere, Hallett eventually found one on eBay—marked up about four times the normal price. “That’s capitalism at its finest,” he says with a laugh.

One crucial piece of equipment in short supply, says Hallett, are the monitors that allow nurses to keep tabs on an ICU patient’s vital signs from outside the patient’s room.

“In a typical ICU, that large monitor screen would be visible through a glass window or wall, so the nurse could check vitals without having to enter the room,” he says.

In his makeshift ICU, only small travel monitors are available, requiring Hallett and his fellow nurses to “gown up” and enter the patient’s room multiple times an hour to check his or her vitals.

But thanks to a company’s donation of baby monitors, Hallett fashioned his own system by duct-taping the camera portion of the baby monitor to the travel monitor’s display, allowing him to see the patient’s information from anywhere in the unit.

“I keep that baby monitor in my pocket and check it more than I check my phone,” he says.

The rules have changed.

In nursing school, Hallett learned one thing above all else: do whatever you can to save a life. “When a patient is coding [experiencing cardiopulmonary arrest], we were taught to do whatever it takes,” he says. “You’d do compressions for hours if necessary.”

But in the midst of the pandemic, Hallett finds himself and his colleagues making a heartbreaking calculation all too often.

“Sometimes it’s more dangerous for the patient and the healthcare workers to continue these interventions,” he says.

For instance, life-saving chest compressions require close contact between the patient and healthcare workers. The virus is easily transmissible through the patient’s bodily fluid and droplets in the air, putting everyone in the area at risk. What’s more: ICU beds are in demand. When one patient is discharged or passes away, there’s a long line of new, severely ill patients waiting to take his or her place.

“It was a rude awakening the first time a patient was coding,” he says. “We did several rounds of compressions and a doctor said, ‘I think we should call it.’”

“I got into this profession to save lives, but in this situation, you have to make difficult decisions for the greater good.”

Optimism is everything.

When a typical day includes delivering the news of a loved one’s death to a family—sometimes in person but more often via FaceTime—it’s not easy to leave work behind at the end of a long shift, says Hallett.

“Dumb stuff” on Netflix helps him decompress, as does Hallett’s self-imposed boycott of Facebook and other social media (Facebook friends who claim the pandemic is a “hoax” are especially grating). And despite leaving behind his fiancé, also a nurse, back in Syracuse, Hallett is joined in his New Jersey apartment by his dog, Oliver.

“It’s nice to have some sort of companionship,” he laughs.

But more than anything else, says Hallett, staying mentally healthy is all about his outlook.

“Strangely enough, this whole situation has made me more of an optimist,” he says. “I’m constantly looking for the good in things. We are discharging patients. In my unit, we have saved 10 patients who have coded.

“I have to keep thinking about the positive,” he says. “Despite everything, people are getting better.”

More Stories

Utica University Delegation Participates in Prestigious Harvard Model UN Conference

Utica University’s Model UN Club competed in the Harvard University National Model United Nations (HNMUN), held last month in Boston....

The Ideal Co-Author

Grace VanEtten ’26 is handpicked by Professor Christopher A. Riddle to share authorship in prestigious bioethics journal

Utica University Opens New State-of-the-Art Cyber Range

Utica University faculty and students, along with dignitaries and industry partners, marked the opening of the University’s new state-of-the-art Cyber...

I would like to see logins and resources for:

For a general list of frequently used logins, you can also visit our logins page.